Emotional ABCs Accelerates Social and Emotional Learning

Among First and Second Grade Students

Phillip Ehret, Ph.D.

September 22, 2020

Abstract

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is a critical developmental process where children acquire and develop the skills, knowledge, and attitudes necessary to manage emotions, develop and maintain relationships, and make appropriate decisions. The purpose of this evaluation was to examine how the Emotional ABCs Program increased students’ social‑emotional competence. Emotional ABCs is an SEL program designed to help children in kindergarten through third grade develop age‑appropriate SEL skills and abilities. The study included 473 students in first and second grade at eight different elementary schools, in 22 different classrooms across the United States. SEL scores were measured at two time points approximately eight months apart, before and after the timeframe in which students participated in the Emotional ABCs Program. All students’ SEL scores increased between the two measurement time‑points, and importantly, students who participated in the Emotional ABCs Program significantly increased their SEL scores by approximately five more points than students who did not participate.

Introduction

Children learn a number of skills and develop abilities throughout childhood that are critical to how they interact with the world around them. One of the most important learning processes they develop is social and emotional learning (SEL). SEL is the process through which children (and adults in later life) develop the skills and knowledge necessary to understand and manage emotions, develop and maintain relationships, and make appropriate decisions (CASEL, 2012). SEL skills are often learned through experience and taught informally by parents, teachers, and peers. However, given how critical SEL is to effective life functioning (Pianta & La Paro, 2003; Raver, 2002), a number of programs have been developed to specifically help children learn and apply social‑emotional skills (see Durlak et al., 2011 for review). The current study is an evaluation of the Emotional ABCs Program, where teachers presented a sequential series of SEL workshops to students. These workshops first build specific SEL skills and then help children learn how to use those skills.

Social And Emotional Learning Programs

SEL programs encourage students to develop their full potential by explicitly teaching social‑emotional skills and focusing on the whole child. Participants demonstrate overall beneficial effects on positive self‑image, social skills, prosocial behavior, and academic achievement. For example, a meta‑analysis of 213 school‑based SEL programs found that students that participated in the programs had less emotional distress, antisocial behavior, and conduct problems, as well as improvements in academic performance that reflect an 11‑percentile point gain in achievement (Durlak et al., 2011). Further, SEL predicts important life outcomes in adulthood (e.g., Jones et al., 2015). (More studies are listed at https://www.emotionalabcs.com/scientific-studies/)

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), a leading authority on SEL, finds that effective programs have the following four components: a) use a coordinated set of activities to achieve skill development objectives (sequenced); b) use active forms of learning to help youth learn and master new skills (active); c) have at least one component devoted to developing social emotional competence (focused); and d) should target specific skills and learning goals rather than positive development in general terms (explicit). Children can develop emotional skills using drawings, games, videos, music, and more (for a detailed overview and discussion of SEL, see CASEL, 2020).

The Emotional ABCs Program

The Emotional ABCs Program is a sequential, skill‑building educational curriculum for children ages 4‑11 developed in collaboration with psychologists, therapists, and educators. The curriculum, which does not require teacher training, includes a set of 20 classroom workshops consisting of short modules for flexible teacher use (see Appendix A for descriptive images of the program). Each workshop uses interactive online activities, videos, printables, as well as in‑classroom teacher modeling, teacher‑student interactions, and student‑student interactions. The curriculum is divided into four units, and each workshop builds on skills introduced in previous workshops. All resources needed per workshop are provided by Emotional ABCs either as online content or as downloadable printables, and each workshop includes a clear SEL Teaching Goal, a Teaching Point with suggested modeling ideas, relevant Group Discussion and Group Activities, plus Individual Self‑Reflection sections. A main feature of the curriculum is the Emotional ABCs Toolbar (see Figure 1), which shows children how to quickly figure out what they are feeling (Pause), why they are having that emotion (Rewind), and how to make a good choice (Play). The clarity and ease of use of the Toolbar allows children and teachers to implement the process not only in the classroom, but schoolwide.

Figure 1. The Emotional ABCs Toolbar

The curriculum includes four content units that students progress through in sequence. The first unit introduces emotional skills, where children learn how to define an emotion, observe their own and others’ emotional responses, develop an expanded emotional vocabulary within a context, observe that emotions can be complex and change easily, and as a summary, use their expanded emotional vocabulary to tell stories. The second unit builds skills to increase emotional understanding by bringing attention to non‑verbal clues to help students interpret their own and others’ emotions. This unit has children consciously focus on face and body visual clues, develop a method of breathing that helps them self‑evaluate their emotional state, become aware of sensations, and learn how idioms can be used to express sensations. The third unit teaches self‑management of emotions. Specially, this unit introduces students to the Emotional ABCs Toolbar, a mental ’short‑hand’ to help remember three essential emotional skills and to use them in the proper sequence. These skills are: 1) Keeping emotions from escalating into difficult‑to‑manage intensity levels (Pause & Breathe); 2) Thinking back through an emotionally intense situation (as dispassionately as possible) to more clearly understand what launched the emotional response (Rewind); and 3) Choosing a course of action that most appropriately addresses the needs of the student (and others) in the specific situation (Play). The fourth and final unit demonstrates approaches for responsible decision‑making by using ’Plays’ from the Emotional ABCs Playbook. Two examples of ’Plays’ that students observe and practice in‑class include The Talk Play—a choice to ’use your words’—and The Fix‑It Play—a choice to fix a problem yourself. The final workshops conclude the curriculum by offering opportunities for students to practice using all learned SEL skills in hypothetical situations presented in the age appropriate world of Moodlandia.

Study Design

Participants

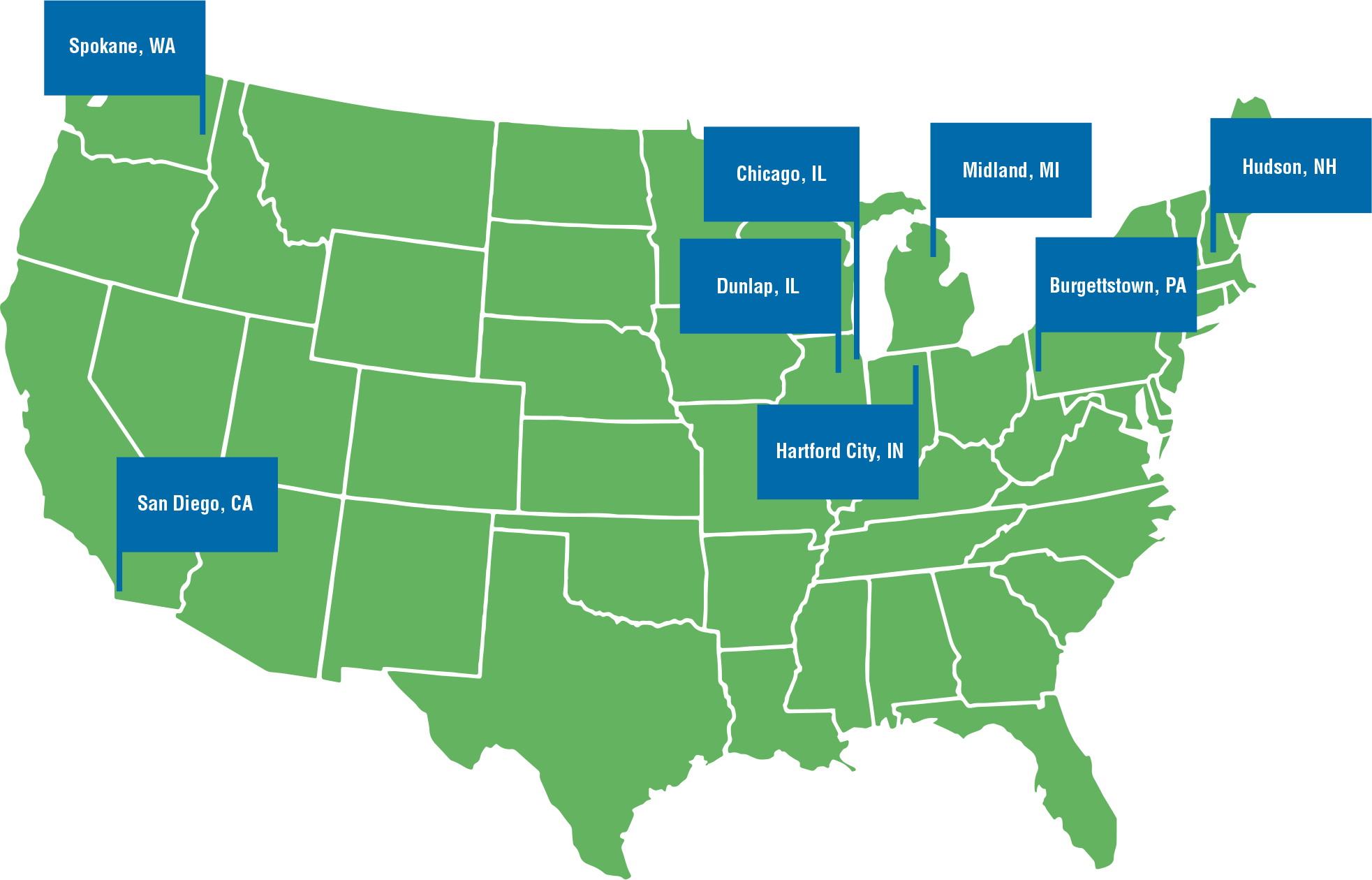

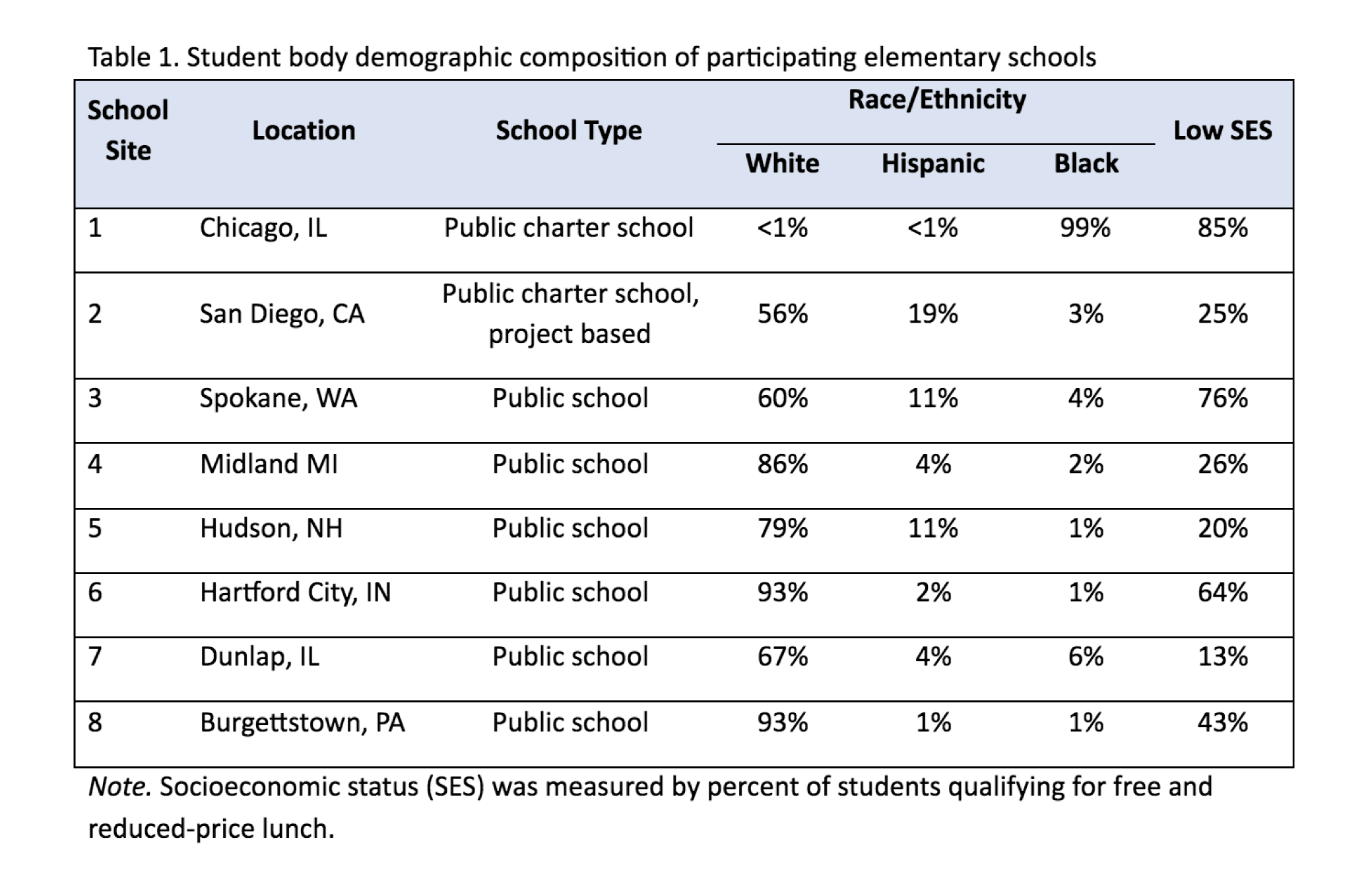

The sample consisted of 473 students, 255 first‑grade students and 218 second grade‑students. The students were from eight schools across the United States and were selected to represent a diverse sample of students. Student‑level demographics were not measured,1 but school‑level demographics were collected for the 2019‑2020 school year as reported from the available individual school profiles on GreatSchools.org and the IllinoisReportCard.com at the beginning of the study. As shown in Table 1, the student body at each elementary school varied across their racial composition and socioeconomic status (as measured by percentage of students qualifying for free/reduced lunch).

Ten classrooms served as the control (5 first grade, 5 second grade classrooms; 213 students), and 12 classrooms implemented the Emotional ABCs (7 first grade, 5 second grade; 260 students); each school had at least one control and one participating classroom. Each classroom was taught by a different teacher. Attrition was very low; one student moved during the school year and was no longer enrolled at the school, and thus they are not included in the final analytic sample.

Procedures

In August and September of 2019, Emotional ABCs staff invited teachers and counselors who had signed up for a free teacher version of Emotional ABCs (which represented over 38,000 schools at the time) to participate in the study. Emotional ABCs staff then contacted the schools of interested teachers and counselors, and offered free access to the online Premium Schools version of the Emotional ABCs Program for the next three years in exchange for their participation in the study. In order to participate, schools must have had general education classrooms where students in those classrooms were randomly assigned and represented a typical cross‑sampling of the school’s student body. Each school that decided to participate then selected at least one of these general education classrooms to participate in the Emotional ABCs Program and at least one other (of the same grade) to be a comparison classroom. The schools were instructed to select equivalent classrooms; however, they were not randomly selected. The Emotional ABCs staff and the evaluator had no input on the actual selection of the classrooms to avoid bias. Since classrooms were not selected randomly, the study was a quasi‑experiment. A total of eight elementary schools, with 22 total classrooms participated in the study.

Teachers providing the Emotional ABCs Program committed to completing at least 15 of the 20‑workshop curriculum. Some teachers taught up to two workshops per week while others broke single workshops down into multiple parts, teaching each workshop over several days. Teachers downloaded or printed out Emotional ABCs resources as best‑suited for their individual classrooms. The complete Emotional ABCs Program curriculum is available at https://www.emotionalabcs.com/classroom/curriculum/.

SEL learning was measured twice for all students, once between October 7th to November 2nd, 2019, before students started the Emotional ABCs Program, and once between May 4th to June 3rd, 2020, after students had completed at least 15 of the 20 Emotional ABCs Program workshops. Note that many schools closed in March of 2020 due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, all participating classrooms had completed at least 15 workshops.

Measures

For both measurement timepoints, teachers completed the Devereux Student Strengths Assessment‑mini (DESSA‑mini; Naglieri et al., 2014) for each student. The DESSA‑mini provides a general measure of a student’s social‑emotional competence. Pre‑test and post‑test scores from the DESSA‑mini (SEL scores) were recorded. Teachers completed the DESSA‑mini assessments directly on the Aperture Education website following the guidelines established by Aperture Education, who administers the DESSA‑mini evaluations. Teachers created non‑identifying rosters to protect student identities.

The DESSA‑mini is a strengths‑based teacher‑report assessment consisting of eight items that describe a number of positive behaviors seen in children. Teachers are asked to report on a scale from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Very Frequently” how often in the past four weeks a child did a specific behavior such as “pay attention,” “contribute to group efforts,” or “do something nice for somebody.” There are four different but equivalent and interchangeable DESSA‑mini evaluation forms. This study used DESSA‑mini #1 for the pre‑test measurement and DESSA‑mini #4 for the post‑test measurement (see Appendix B). The eight‑item forms are standardized, and each student’s social‑emotional total score (T‑score; M = 50 and SD = 10) provides an indication of the strength of a child’s social‑emotional competence, based on comparison to national norms. The DESSA‑mini quantifies competence along a continuum from a clear need for instruction to proficiency. T‑scores of 60 and above are referred to as strengths (high social‑emotional competence). T‑scores that fall between 41 and 49 inclusive are described as typical social‑emotional competence. T‑scores of 40 or below are described as a need for instruction (low social‑emotional competence). Additionally, changes in T‑score units directly relate to effect sizes, with a score change of 2 to 4 points corresponding to a small effect size, 5 to 7 corresponding to a medium effect size, and 8 or higher corresponding to a large effect size (see Naglieri et al., 2014).

Results

First, descriptive statistics were calculated for the pre- and post‑test SEL scores. Pre‑test SEL scores ranged from 28.00 to 71.00, and the average pre‑test score was 49.87 (SD = 11.53). There was no significant difference of pre‑test SEL scores between condition (Emotional ABCs: M = 49.51, SD = 11.36; Control: M = 50.32, SD = 12.04; t = 0.75, p = .449). Post‑test SEL scores ranged from 29.00 to 72.00, and the average post‑test score was 55.05 (SD = 10.42); this reflected a general pattern that all students, on average, increased their SEL scores between the pre‑test and post‑test.

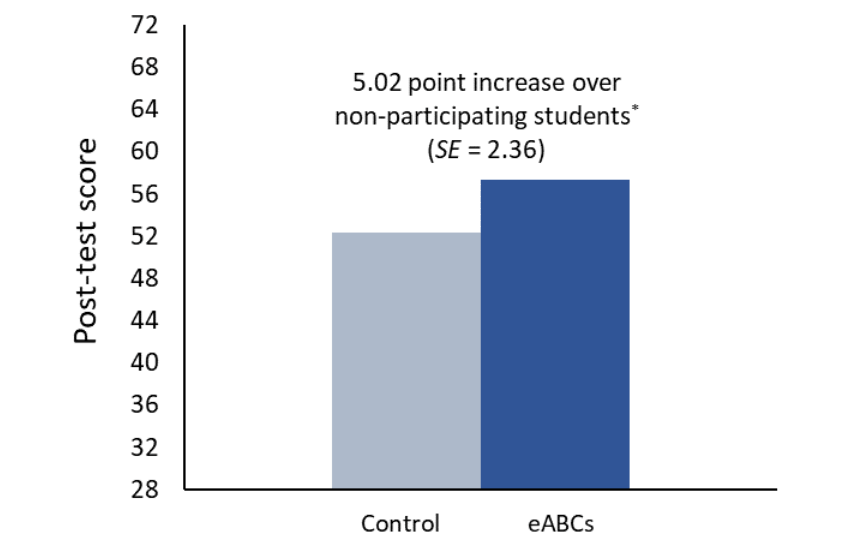

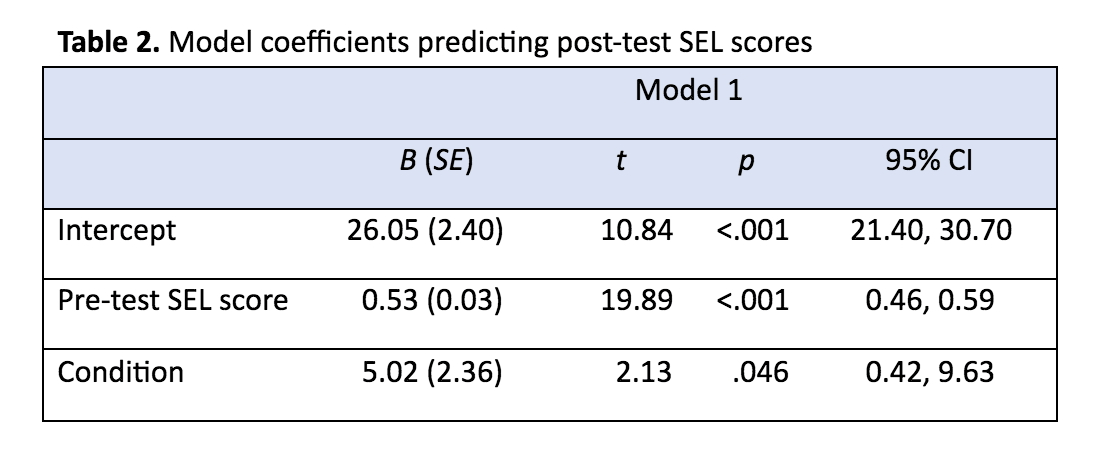

Next, the focal analyses used a linear mixed‑effects model to test for a relationship between participating in Emotional ABCs and SEL scores (Model 1). This primary model included pre‑test SEL scores and condition (0 = control, 1 = Emotional ABCs) as the predictors, and post‑test SEL scores as the outcome; classrooms were entered into the model as a random effect. Model coefficients are reported in Table 2. There was a significant relationship between pre‑test SEL scores and post‑test SEL scores (B = 0.53, SE =0.03, two‑tailed p < .001), such that students with higher pre‑test scores had higher post‑test scores. Beyond this general relationship between pre- and post‑measurement SEL scores among all students, the model found a significant effect of condition (B = 5.02, SE = 2.36, two‑tailed p = .046).2 Students that participated in Emotional ABCs increased their SEL scores, on average, by five more points than students who did not participate (see Figure 2). Based on established effect sizes for the DESSA‑mini measure (Naglieri et al., 2014), this is considered to be a medium effect.

Figure 2. Difference in SEL scores between students who participated in Emotional ABCs

and those who did not

Note, figure shows estimated post‑test SEL scores at the average pre‑test score (49.87). * two‑tailed p < .05.

Conclusion

Students that participated in the Emotional ABCs Program increased their social‑emotional competence compared to their peers that did not participate in the program, above and beyond the typical score increase seen among all students over time. This significant increase corresponds to a medium sized effect, indicating that the Emotional ABCs Program had a meaningful impact on students who participated. Aperture Education, leaders in the administration of SEL measurement, describe a medium effect as indicative of a program doing a “decent job of implementing social and emotional learning activities,” and that an outcome of this magnitude over a single year meets the criteria for a successful SEL program (Aperture Education, 2020).

In addition to the beneficial effect of the Emotional ABCs Program, the program holds particular promise as it is self‑contained and does not require any additional teacher training or dedicated preparation outside of the time students are actively participating. Research has found that teachers often recognize the value of SEL, but do not feel they are adequately trained to support SEL (Hemmeter et al., 2008). Emotional ABCs provides a SEL development solution that does not require additional training before implementation. Additionally, the program can be adapted to meet a teacher’s needs and overall curriculum. The Emotional ABCs curriculum is flexible and can be delivered over a few months or spaced out over an entire school year, and the program offers support for teachers to develop their own follow‑up workshops to reinforce learnings beyond the provided 20 workshops.

There are some important limitations to consider with this study. First, students were not randomly assigned to condition. Although efforts were made to select equivalent classrooms for Emotional ABCs and comparison students, there may have been unmeasured systematic biases between the two groups. Additionally, there were no other student‑level data collected beyond SEL scores, limiting the ability to control for other potential confounds. There was also variation in how teachers administered the Emotional ABCs Program. Although this adds additional variance between classrooms, this variance would be expected in any large‑scale deployment of the program and likely leads to a conservative test of the effect of the Emotional ABCs Program. Nonetheless, future evaluations should seek to use a randomized controlled trial design that also accounts for differences in the delivery of the Emotional ABCs (e.g., dosage and fidelity). This would increase the confidence in the effects of the program and potentially reveal other factors that boost the effect of the program.

Despite these limitations, the Emotional ABCs Program had a beneficial and meaningful effect on students that participated, and the study suggests that Emotional ABCs can be a useful and easy‑to‑implement tool for teachers who want to support their students’ social‑emotional development.

Footnotes

1 To increase school participation, no potentially identifiable information at the student level was collected.

2 Additional models included school‑level covariates of race and SES, as well as student grade (first or second grade); none of these covariates had a significant effect on post‑test scores, and the inclusion of these additional covariates did not change the estimated magnitude of the effect of the Emotional ABCs Program.

References

Aperture Education. (2020, September 16). What amount of change should be expected in a student’s full DESSA and DESSA‑mini results? https://selcompass.zendesk.com/ hc/en-us/articles/209611186-What-amount-of-change-should-be-expected-in-a-student-s-full-DESSA-and-DESSA-mini-results-

CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning). (2012). Effective social and emotional learning programs. Chicago, IL: Author

CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning). (2020, September 15). What is SEL? CASEL. https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‑analysis of school‑based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405‑432.

Hemmeter, M. A., Santos, R. M., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2008). Preparing early childhood educators to address young children’s social‑emotional development and challenging behavior: A survey of higher education programs in nine states. Journal of Early Intervention, 30, 321‑340.

Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early socio‑emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283‑2290.

Naglieri, J. A., LeBuffe, P. A., & Shapiro, V. A. (2014). Devereux student strengths assessment. Devereux Foundation.

Pianta, R. C., & La Paro, K. (2003). Improving early school success. Educational Leadership, 60(7), 24‑29. Raver, C. C. (2002). Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Report of the Society for Research in Child Development, 16(3), 3‑19.

Author Biography

Dr. Phillip Ehret is a behavioral scientist and specializes in the design and evaluation of behavioral interventions. He received his Ph.D. in Social Psychology with an emphasis in Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences from UC Santa Barbara. Central to his research and consulting approach is his desire to leverage behavioral science theory to create meaningful and lasting change to address society’s most pressing issues. He has worked on interventions in a variety of domains, including education, health, and sustainability.